'Just' Market Prices: Rafael Termes's Reappraisal of the Thomistic Just Price Doctrine

Rafael Termes's interpretation of Aquinas offers an original account of the dynamic justice of market order

Rafael Termes’s interpretation of Aquinas on the just price illuminates how we think about the dynamic justice of market order, where the market process justly prices in the context of exchange and enriches liberty.

In contemporary conservative thought, there is a growing tendency to invoke Thomistic moral philosophy to critique free markets, often through an appeal to St. Thomas Aquinas’s doctrine of the just price. Figures across the political spectrum, but particularly those advocating for economic interventionism on moral grounds, argue that Aquinas’s vision of economic justice is incompatible with the market-driven determination of prices. Such positions tend to perceive the market economy as a necessary evil, and prices the result of abuse and exploitation.

It seems a normal routine today to cry out “price gouging!” when finding unexpected price increases of staple products. For example, the recent spike in egg prices in the United States due to the bird flu outbreak was perceived as price gouging. Not surprisingly, “price gougers” become the public enemies of a society that passes through outstanding circumstances: economic crises in the mid-70s and 2008, as well as during natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, pandemics, or wildfires. The specific concept of “price gouging” is relatively new:

However, the apparent injustice of price increases by profit-seeking merchants has been a matter of discussion since ancient times. Aristotle famously argued that trade should aim at a reciprocal equality, granting equal benefit to both parties, and criticized those who sought to exploit the necessity of others.

Aquinas follows Aristotle, to a point. But a common error today is to wield the Thomistic doctrine on the just price as an argument against the supposed cold-hearted nature of markets, incorrectly simplifying both the Summa Theologiae’s wisdom and our understanding of the market as a complex social system, or a spontaneous order. Such an anti-market faux-Thomistic approach can conclude that fraud and abuse are fundamental for markets to work. This way, political commentators on the right might justify government intervention to prosecute whatever appears as price gouging, without realizing that effective price ceilings, instead of protecting the consumer, exacerbate the shortage problem intended to be solved in the first place.

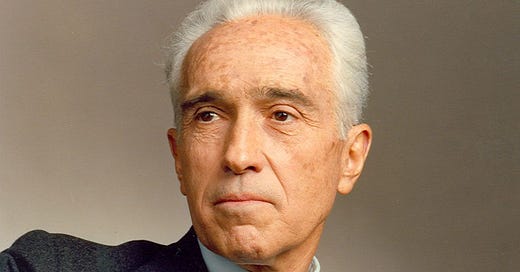

I find in Rafael Termes’s work a profound yet simple interpretation of Aquinas’s just price doctrine that could be helpful to those interested in the just price doctrine, and how it might apply today. Rafael Termes (1918–2005) was a Spanish economist and banker known for his contributions to the defense of economic classical liberalism within the framework of Catholic social teaching.

In Antropología del Capitalismo, one of his key works, Termes explores the ethical and anthropological foundations of free-market economics. He offers a unique and modern approach to the moral question of markets, yet he is not isolated: his work aligns well with that of Michael Novak or Wilhelm Röpke. Termes follows the interrelatedness of ethics and markets through the writings of Aquinas, the Salamancan interpretation of the Thomistic just price doctrine, and the contributions of 20th-century market process economics.

Termes reinterprets Aquinas, based on an updated (post-marginalist) understanding of what the free-market process is. Termes first points out that Aquinas recognized the tendency of exchange to happen for mutual benefit, and apart from fraud, the price would be just if the mutual benefits from trade are equivalent. Termes, however, notices that Aquinas was aware of the subjective nature of human needs and utility, thus allowing for a varying market price based on subjective utilities that is neither static nor precise. According to Aquinas, “the just price of things is not fixed with mathematical precision, but depends on a kind of estimate, so that a slight addition or subtraction would not seem to destroy the equality of justice.”1

Termes expresses clearly how the Thomistic approach allows for just prices to adjust by varying circumstances. Extreme conditions, from pandemics to bird flu outbreaks to wildfires, change the circumstances people must face. Individual priorities, preferences, and thus relative scarcities of goods can change rapidly, and price increases provide essential, tacit information to the market. It is as common for the concept of “price gouging” to resurface as the consequential wave of responses from economists pointing towards Hayek’s “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” In this way, the market process prices in the context of exchange. As Termes writes:

… (Aquinas) recognizes that prices depend on a set of factors that can influence their estimability. Among these, he cites the differences in place and time, the rarity and preciousness of certain goods, the scarcity of necessary items at the point of sale, and the size of supply relative to demand. Thus, Aquinas establishes that the common or market price, freely negotiated in the absence of violence, fraud, or deceit, is the just price.2 (emphasis mine)

The usual interpretations of the just price doctrine are partly wrong, not due to a misunderstanding of Thomism, or justice, but from a misconception of what free-market prices truly are. If we follow Termes’s reappraisal of the Thomistic doctrine, Aquinas’s just price is simply the free-market price with extra steps. It seems true, if one endeavors to explore the available data and compare across different measures of market societies (as Virgil Storr and Ginny Choi do in their Do Markets Corrupt Our Morals?), that societies which have a relatively higher respect for free and voluntary market transactions (including those that include very high prices) tend to be more just, healthier, happier and better connected.

The market process, as understood by Termes and expressed in his works, is a system based on the protection of private property, without any centrally devised intervention on prices, and a presumption of liberty that allows for private individuals to have a say in the solutions to their local problems. This includes both adjusting voluntarily to price increases, and the freedom to pursue profit without fraud or deceit.

The great merit of the protection of property within a free-market system is a profound respect for liberty. It is true, as Termes recognized, that for a flourishing society liberty is not enough, but also putting liberty in relation to what is good. That is, as Termes pointed out, the duty of all Christians that enjoy freedom. On this, Termes used to invoke Tocqueville’s words: “Tocqueville expressed it wonderfully by saying ‘freedom is a holy thing.’ There is only one other thing worthy of that name: virtue. But what is virtue, if not the free choice of good? That is why, although good cannot be imposed, it is desirable for man to be voluntarily good.”

Eugenio Garza is a third-year PhD student in economics and a graduate lecturer and fellow at George Mason University. His research interests include economic development, political economy, economic sociology, philosophy, and ethics. He is from Monterrey, Mexico.

Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II-II, q. 77, a. 1, ad. 1.

Rafael Termes, Antropología del Capitalismo (Madrid: Ediciones Rialp, 2001), 86.

"Aquinas establishes that the common or market price, freely negotiated in the absence of violence, fraud, or deceit, is the just price."

Again, everything hinges on what constitutes a free negotiation. It's more than just the absence of violence, fraud, and deceit, as Aquinas well knew. Adam Smith establishes that a free negotiation is one where all parties in the economic transaction are free to reject the transaction. If some of the parties cannot afford to abandon the contract, that provides negotiating leverage to the other parties, and is no longer a free negotiation.

A nice example has been in the news lately regarding the U. S. and Ukraine. Ukraine needs military support to sustain a defense in a just war against Russia. The United States has been trying to get Ukraine to sign a rare earth minerals contract that would disproportionately advantage the U. S. This is not a free negotiation, because the U. S. is using the existential threat to Ukraine as leverage to coerce them into making the deal.

More than 90% of all market prices are not negotiated under a complete set of conditions for free negotiation, and therefore do not reflect just prices. A wider survey of Aquinas' discussion of distributive justice is consonant with this analysis.