Juan de Mariana: Precursor of Classical Liberalism

Juan de Mariana’s political theory expands our conception of the classical liberal tradition and its roots in religious thought

By Matthew P. Cavedon

A philosopher and theologian in the School of Salamanca, Juan de Mariana’s political theory expands our conception of classical liberal ideals beyond Anglo-American theorists — and that tradition’s roots in religious thought.

Introduction

Overreliance on Anglo-American intellectualism deprives us from grasping other important foundations of classical liberalism. In the early modern era, theologians associated with Spain’s University of Salamanca rejected the rise of absolutism based on natural law philosophy. They defended moral constraints on government based on the nature and end of political power. Their work deserves to be better remembered as a landmark contribution to thinking about the rule of law and public liberty.

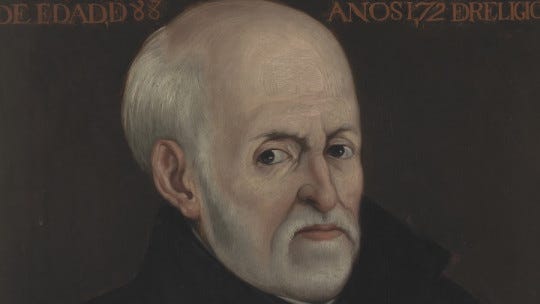

Perhaps the most radical member of the School of Salamanca was the Jesuit priest Juan de Mariana, born in 1536. His best-known work, De Rege et Regis Institutione (On the King and the Education of the King), was published in 1598. Its defense of tyrannicide caused a sensation and had a major impact on French politics. In this essay, I will give an account of Mariana’s political theory, showing how it expands our understanding of the sources of classical liberalism beyond the Anglo-American tradition.

In formulating his political theory, Mariana drew direct inspiration from a then-recent regicide. In 1589, French king Henry III was fatally stabbed by a fanatical Dominican friar following his execution of two leading critics.1 The assassin was drawn and quartered before the king was even dead,2 but was soon venerated in French churches.3 Mariana referred to him as “an eternal glory of France.”4 However, King Henry IV, far more popular than his predecessor, was killed twelve years later, and though Mariana never endorsed this second slaying, he nevertheless remained controversial long after his death in 1624.5

Nature, Reason, and Government

De Rege begins with an idealistic discussion of the original state of humanity. Mariana imagines that people were able to live in peace and plenty, never needing to work hard or resort to violence. People were ordered to perfectly love God and their fellow humans. That perfect existence disappeared with the advent of sin, which introduced suffering and division into the world.6 Human beings remain naturally social, even if they are not inclined to act kindly. In order to induce people to feel their need to love and be loved by others, God permits people to experience needs that they cannot satisfy by themselves. Society emerges as a result.

Exigencies faced by societies give rise to government.7 Historically, people found that they needed a monarch in order to live better within the republic, so they chose a single chief to defend them against their enemies and uphold justice. Owing to its ability to win the consent of naturally free people in ancient history, Mariana argues that monarchy is the most natural form of government.8 The monarch has uncommon dignity and power because life under a common set of laws necessitates their exclusive ability to fight danger and injustice. Monarchs are unlimited in their legal right to do these two things.9

Mariana believes, though, that a republic ought to be governed by reason, law, and its subjects. Reason can determine that absolute rule by a single person is ineffective at establishing justice and prone to corruption. Only with many people participating in public life can the government gather the information necessary to meet common needs, and a multitude of active citizens can safeguard against the monarch’s corruption.10 Mariana also believes that all government depends on the people: “the authority of the community, when all have reached a common accord, is greater than that of the prince.”11

Mariana regards custom as another important limit on power. “[I]t is dangerous to alter our national institutions, even when our convictions rebel against them.”12 As for absolutism, “legitimate princes must never work in a way that seems to be the exercise of absolute sovereignty disconnected from the law.”13 Law includes popular customs, and the monarch is not free to alter or depart from them without legislative consent.

Mariana’s defense of the rule of law holds true even for laws passed by the monarch. Laws oblige their makers—even if in extreme cases forcing monarchs to obey the law necessitates killing them.14 It is not merely a crime, but also a scandal and an abnegation of duty, for the monarch to violate the law.

Tyranny and Resistance

Mariana considers it logically necessary that tyranny—the worst form of government—be the opposite of monarchy, the best kind of government.15 The monarch defends the innocent and the welfare of every subject, being “humble, tolerant, accessible, and amiable to living under the same law as everyone else.”16 The monarch exercises power well for the sake of the common good.

By contrast, a tyrant is one who enjoys power through force, intrigue, or riches, rather than virtue or popular consent. Tyranny “constitutes its power freely for the unlimited entertainment of its passions, finds no evil to be indecorous, commits every type of crime, destroys the homes of the powerful, violates chastity, kills good men; there is no violent action it will not commit given a long enough life.”17 The tyrant exercises power in a heavy-handed, judicious, prejudiced, and self-interested way. “The tyrant, distrusted by the people, is fearsome, amiable to terrorizing [them] with his apparatus of power and his fortune, with the hard severity of custom and the inhumanity of his judgments.”18 The tyrant is no monarch, because the monarch has humility and justice and the defense and benefit of the subjects are monarchy’s virtues.

Monarchs fear demagogues, but tyrants fear the people.19 The tyrant lacks their consent and seeks to maintain power against them. The tyrant will often ban political association and seek the aid of foreign rulers and even mercenaries, knowing that their purchased help is necessary for maintaining control.20 Tyrants often try to persecute the most honored, richest of the subjects to curb their influence. The tyrant tries to buy the support of the people with grand tributes, wars of conquest, and expensive monuments.21 Tyrants can gain power legitimately or otherwise, but either way, they use it for their own benefit rather than that of the public.22 The monarchy exists by the consent of the people, who retain their rights to change the fundamental laws and confirm their election of an hereditary royal at coronation.23 “The power of the prince is very weak when he loses the respect of his vassals” and every legitimate monarch seeks to maintain popular consent through justice and virtue.24

“The tyrant is like a fierce and inhuman beast,” and it is the duty of people with the means to do so to kill him.25 Abuses against the fatherland should no more be tolerated than those against one’s actual parents.26 This is not to say tyrannicide was Mariana’s preferred option. Whenever possible, a public assembly ought to convene, refuse the tyrant recognition, and take up arms to prevent retaliation.27 Whenever the tyrant makes this impossible, the people should publicize the tyrant’s abuses, urge resistance by wise and prudent people, and have the glorious courage to risk their lives for their country.28

But a ruler who strikes back rather than abdicating is warring against the people and can be killed.29 “If all hope has been lost, and the public welfare and the sanctity of religion are in grave danger, who would not understand and confess that it is licit to depose a tyrant by reason of the right, of the laws, and of arms?”30 Custom and tradition honor those bold enough to risk everything in opposing a tyrant. In Greco-Roman literature and later Christian memory, “it is glorious to exterminate infamous monsters from human society.”31

Conclusion

Popular consent, participatory governance, and resistance to tyranny are all central ideals of classical liberalism. However, these did not originate with John Locke or Thomas Jefferson. The Anglo-American tradition followed the legacy of Mariana, his fellow contributors to the School of Salamanca, and these thinkers’ own earlier forebears.32 Mariana’s critique of tyranny illuminates how we think about the foundations of classical liberalism beyond Anglo-American theorists. Classical liberalism is just one branch on a freedom-minded tree that has been growing in the Western world for over two millennia. Like the American Founders centuries after him, Mariana affirmed that “when a long train of abuses and usurpations” subjects a people to “absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”33

Matthew P. Cavedon is Robert Pool Fellow in Law and Religion, Emory University Center for the Study of Law and Religion. This essay was adapted from his thesis submitted for his 2011 bachelors degree at Harvard College. This adaptation was supported by funding from the McDonald Agape Foundation and Center for Religion, Culture & Democracy.

Fernando Centenera Sánchez-Seco, El Tiranicidio en Los Escritos de Juan de Mariana: Un Estudio sobre Uno de los Referentes Más Extremos de la Cuestión (PhD diss., Universidad de Alcalá, 2006), 357.

Ibid., 359–60.

Ibid., 371.

Ibid., 367. Translations into English are by the present author.

Ibid., 4–5.

Juan de Mariana, La Dignidad Real y la Educación del Rey (De Rege et Regis Institutione), ed. Luis Sánchez-Agesta (Madrid: Centro de Estudios Constitucionales, 1981), 20.

Ibid., 20–25.

Ibid., 28–30.

Ibid., 26–27.

Ibid., 33.

Ibid., 98.

Ibid., 34.

Ibid., 108.

Ibid., 112–14.

Ibid., 38.

Ibid., 61.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., 66–68.

Ibid., 68.

Ibid., 67.

Ibid., 66.

Ibid., 77.

Ibid., 71.

Ibid., 78–79.

Ibid.

Ibid., 80.

Ibid., 81.

Ibid., 80.

Ibid., 83.

Ibid., 87.

See, e.g., Matthew P. Cavedon, “Early Stirrings of Modern Liberty in the Thought of St. Thomas Aquinas,” Politics and Religion 16, no. 4 (2023): 567.

Declaration of Independence: A Transcription, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

Thank you for bringing attention to this neglected thinker. Mariana was also a major figure in political economy, writing against the debasement of currency, a topically important theme in our inflationary age. A translation of this treatise on money can be found in the 2002 issue of the Journal of Markets and Morality.