Classical Liberalism and the Metaphysics of Community

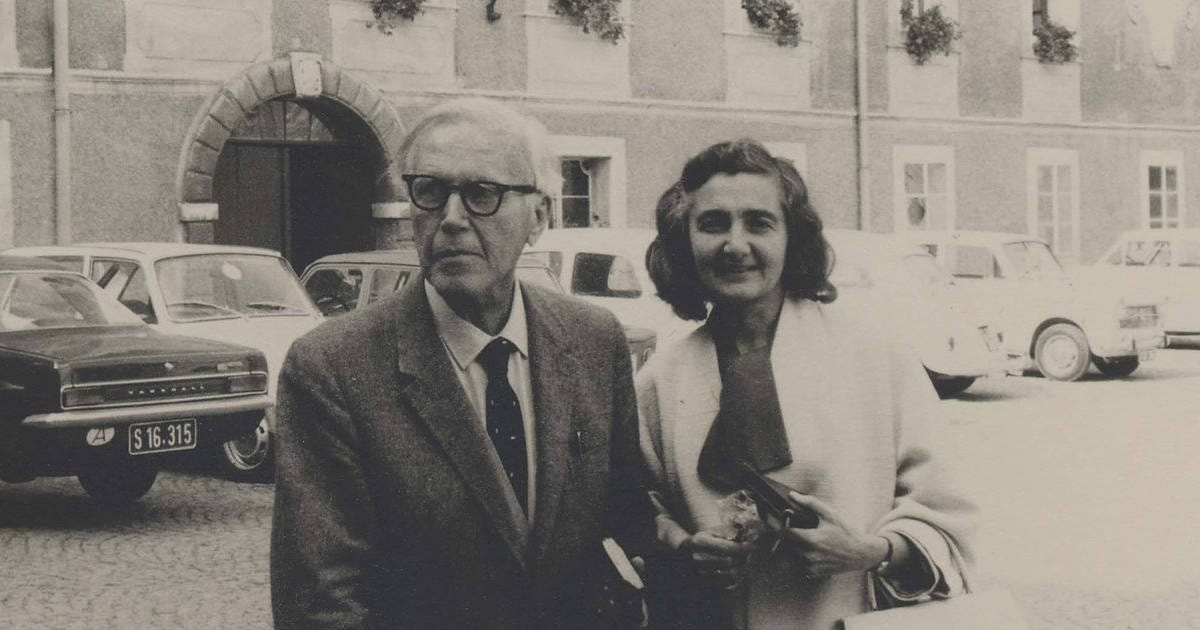

Dietrich von Hildebrand's value-based communities are found in free societies

In today’s age, many have drawn attention to liberal society’s lack of authentic community. The purely instrumental relations that comprise so much of our lives have expanded from the extended marketplace and into our professional and private lives. Dietrich von Hildebrand, one of the most illustrious Christian phenomenologists of the 20th century, can help us analyze this problem. In The Metaphysics of Community, Hildebrand articulates an account of community at a metaphysical level, knowledge of which can be applied to the task of making more meaningful relationships and communities.

In this work, Hildebrand develops a sophisticated taxonomy of community types that illuminates how different social arrangements can foster varying depths of human connection. He identifies three fundamental types of community, all generated by different kinds of relationships. The most basic level of community is called a “life-circle,” formed simply by proximity and circumstance, where members merely acknowledge each other’s existence without deeper bonds. The next level consists of “associations,” which are formally constituted groups established through legal or organizational frameworks. Finally, there are “value-based communities,” which represent the deepest form of connection, where members are unified through their shared response to particular objective values. Hildebrand further distinguishes between “material” and “formal” relations of community. Material relations emerge from direct personal connections and shared value responses, while formal relations are structured through legal or institutional frameworks.1

This framework can be applied to the economic, civic, and professional communities of our lives, especially in describing the nature of the relationships that constitute them. For example, economic social acts such as buying groceries at a grocery store are some of the most common types of economic exchanges that we conduct, but these only generate the spiritually poorest kind of community, the “life-circle” where the customer and employee are merely brought together by external life circumstances and do not go deeper than acknowledging the existence of one another.

Furthermore, within professional communities, such as for-profit companies, many of us do things that do not matter much to us except for the fact that they pay us. In addition, we may work with people with whom we are brought together in a merely formal rather than material or value-based way. While these companies produce wealth that all of us enjoy, they typically constitute the type of communities which Hildebrand calls “associations,” because their constitution is founded primarily on formal and legal relations as opposed to material and value-based ones.

In the classically liberal society, however, there exists an abundance of economic, civic, and professional communities that go beyond mere “associations.” Value-based non-profit organizations exemplify this. These organizations are unique in that they are legal corporations containing relationships that transcend the spiritually lowest kinds of communities described by Hildebrand. Instead, they produce what Hildebrand calls “value-based communities.” In these non-profits, people become involved with one another because they share a response to an objective value, which produces all sorts of value-based relationships. Donors, executives, employees, volunteers, program and service recipients and all else on board come together because they are driven by some moral, intellectual, or aesthetic cause. This provides rich soil for deeper relationships to be formed among participants who care about the same cause.

For example, take an organization dedicated to environmental conservation. Members are bound together by their shared commitment to the moral value of the environment at stake. In a scientific lab, participants are brought closer to one another by a shared response to the call of truth and goodness found in scientific inquiry. For a group of artists on an indie record label (which could also be for-profit) or at an art school, the members of these communities are enriched by the unifying force of their mutual aesthetic values. Religious communities are built and strengthened through shared responses to all of these kinds of value.

How can we encourage the development of more of these value-based public communities in society? Classical liberal political economy can help. Low taxes and a limited welfare state means that private individuals can use their additional wealth to fund more initiatives based on moral, intellectual, and aesthetic values rather than just profit. These initiatives have many benefits for society. As Wilhelm Röpke writes in A Humane Economy:

It is quite obvious that larger incomes (and larger wealth) have so far mainly been spent for purposes which are in the interests of all. They serve functions which society cannot do without in any circumstances. Capital formation, investment, cultural expenditure, charity, and patronage of the arts may be mentioned among many others. If a sufficient number of people are wealthy and if they are dispersed, then it is possible for a man like Alexander von Humboldt to pay out of his own pocket for scientific ventures of value to everyone or for Justus von Liebig to finance his own research. Then it is possible, too, that there should be private teachers’ posts and thousands of other rungs on the ladder on which the gifted can climb and the very variety of which makes it much more likely that some help will be forthcoming somewhere whereas in the modern welfare state their fate depends upon the decision of one single official or upon the chances of one single examination.2

Röpke cites Alexander von Humboldt’s positive contributions to ventures of value in society based on his wealth. Indeed, Humboldt also used part of his large inheritance to open a mining school that taught working-class miners geology, mineralogy, mathematics, the use of safety equipment, and new excavation techniques — an instance of wealth creation serving higher purposes that benefit all.

It’s also helpful to compare the United States with Europe on this topic. In the U.S., non-profit organizations flourish as individuals donate on average $1,427 to charitable causes, compared to an average of just $334 for the Western European countries studied.3 With its more classically liberal economic structure, the U.S. has developed a robust ecosystem of privately funded non-profit organizations that employ almost 10% of the workforce. These institutions don’t just provide services — they create spaces for value-based communities to flourish among their members. European societies, despite large social welfare systems, have seen comparatively less development of such private philanthropic institutions, due largely to higher taxation limiting private initiative. The United States being more religious than Western Europe also helps boost the non-profit sector here as religious individuals have much higher rates of charitable giving than secular individuals.4

To conclude, if we seek deeper and more meaningful value-based work and community, we should create conditions for non-profit and other value-based organizations to flourish, and that means considering a more classically liberal political economy. When people have extra wealth (which is more common in a free society), they give it away to causes based on values they find meaningful. The organizations initiated by these philanthropic efforts then create richer communities among their members, as they are brought together by shared moral, intellectual, or aesthetic values instead of merely formal or economic reasons.

Dietrich von Hildebrand, The Metaphysics of Community (Steubenville, OH: Hildebrand Project, forthcoming).

Wilhelm Röpke, A Humane Economy: The Social Framework of the Free Market (Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery Company, 1960), 168–169.

Pamala Wiepking, “The Global Study of Philanthropic Behavior,” Voluntas 32 (2021): 194–203.

Kidist Ibrie Yasin, Anita Graeser Adams, and David P. King, “How Does Religion Affect Giving to Outgroups and Secular Organizations? A Systematic Literature Review,” Religions 11, no. 8 (August 2020): 405.

Love this!