Against Against Against Against Against Against Against Christian Civilization

A Response to Paul Kingsnorth's Recent First Things Lecture

You may have, before reading this sentence, counted the number of “againsts” in the title of this essay. If there were an odd number, it would connote that I ultimately come down negatively on Christian Civilization, but if there were an even number, I come down positively. If you did count, I regret to inform you that the number I chose was due to constraints on space. If unconstrained, I would have continued indefinitely. It is difficult to come down in a principled way for or against such a massive, uncertain, and nebulous object which has variably brought forth blessings and curses. The infinite sequence of againsts is to connote that nevertheless we ought to inhabit the tension between the blessings and curses of being a Christian in, but not of, the world. This tension echoes the Chalcedonian formulation of Christ’s natures that he is “recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” A series of negatives is used to describe the tension without breaking the mysterious unity of the Incarnation.

Paul Kingsnorth recently gave the Erasmus Lecture at First Things titled “Against Christian Civilization.” Kingsnorth is against the present wave of thinkers hoping to return Western civilization to its Christian roots, sometimes without being confessing Christians themselves. His talk is in some ways a textbook sermon, reminding Christians to live up to the principles that they espouse and to reflect on their shortcomings. He points to some of Christ’s more radical statements such as to give away all one’s possessions to the poor, and reminds us how starkly these are stated. No exceptions are suffered. “Every single one of these teachings, were we to follow them, would make the building of a civilization an impossibility so what we’re really hearing about when we hear talk of defending or rebuilding Christian civilization is not Christianity and its teachings at all, but modernity. And its end game is the idol of material progress.” For Kingsnorth, civilization is a boundedly material and worldly object. If a Christian were to take his faith seriously, it would be tantamount to rejecting civilization as a whole.

But perhaps more interesting than the talk were the questions afterwards. The audience seemed sympathetic with Kingsnorth but ultimately frustrated. The questioners wondered what Kingsnorth was practically suggesting Christians do. One asked from the perspective of someone working for the incoming Trump administration. Are they to quit their job? If so, what are they to do otherwise? One way Kingsnorth responded was to say that he favors Christian culture, which he distinguishes from Christian civilization. Granted, if one defines Christian civilization as all the complications that come from life in the world, and Christian culture as all the blessings, then they’ve solved the debate tautologically. Yet this still dodges the remaining question of what we are to do with our feet and our funds tomorrow. Which public acts of Christians are “civilization” and which are “culture”? One questioner asked about the image in the book of Revelation of a city which might suggest a positive vision of a Christian civilization. Kingsnorth (having anticipated the question) responded that the city is not built by human hands but descends from above (Revelation 21:10). Jonathan Pageau in a separate conversation responded that though the city descends from heaven, the kings of the nations bring their splendor and glory into it (Revelation 21:24-26). One can go on and on in circles, never settling on either side of the debate.1

At each turn there is a genuine risk, warranting another round of againsts. If one is too confident in erecting some pillar on behalf of Christ, they risk building a tower of Babel only to see it collapse under the weight of their own pride. If one is too afraid to have their faith influence their decisions in the world, even decisions of little consequence, one risks becoming like Jonah. Jonah was called to go to Nineveh, the height of worldly power and wealth, and call on the people to repent. Jonah hesitates to involve himself with the worldly authorities, ultimately to have God spit him out in their direction.2 The extreme positive and negative positions toward civilization seem to have Biblical counter-examples. But where is the golden mean?

The classic example of the Christian bargain with civilization was the conversion of emperor Constantine and the resultant transformation of both the church and the empire. The figure of Constantine naturally attracts controversy. What was the emperor’s role in the Church to be? How were bishops to relate to their newfound secular duties? Fr. Georges Florovsky comments:

The leaders of the Church were compelled, time and again, to challenge the persistent attempts of Caesars to exercise their supreme authority also in religious matters. The rise of monasticism in the fourth century was no accident. It was rather an attempt to escape the Imperial problem, and to build an ‘autonomous’ Christian Society outside of the boundaries of the Empire, ‘outside the camp’.3

The monastics represent a curious development coextensive with the controversies of the fourth century. After Constantine, we see bishops move closer to civilization, but we also see the monks move further away.

But the monks and bishops do not schism into two separate bodies. They remain in conversation with one another. The monks respect the authority of the bishops, but since they have extracted themselves from civilization, they have the capacity to reject bishops who they believe have capitulated to the world. When a monk bowed before a bishop, he did not do so because he was seeking any material benefit. He could make credible signals about which bishops remained holy and which had been tainted by the empire. The bargain with the emperor was not inherently tainted, but certainly came along with ambiguity and risk. The monastic mission might be thought of as an insurance policy, purchased by the church to ensure the continuity of the faith despite the hierarchical flirtation with the empire.

Kingsnorth repeatedly turns to the monastics as examples of uncivilizational Christians. They are proof that rejection of civilization is possible. But what Kingsnorth misses is that the monastics are never the whole of the church. St. Anthony, before he leaves for the desert, is sure to take care of his worldly affairs, and provides for his sister for whom he is responsible. He was able to live a life outside civilization in some ways because he was wealthy, making his decision to sacrifice his wealth all the more powerful. By minimizing, or at least stabilizing, the ways that a monk relates to civilization, he has created “laboratory conditions” for spiritual development. The discoveries he makes in the lab about his inner life can then benefit those practitioners outside the lab.

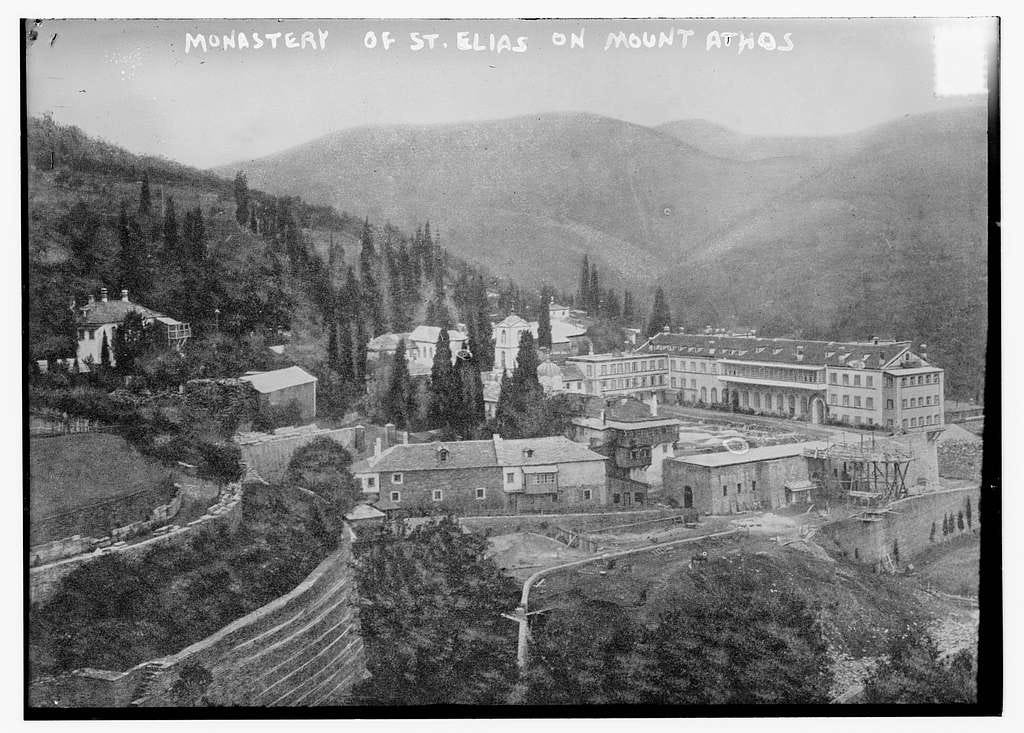

The monastic life is certain to play a role in whatever challenges Christians face in the coming decades, but there are unfortunately too few examples of the religious life today. Since the Reformation, many European kings decimated their monastic population and various intense persecutions have decreased the monastic footprint around the world.4 Looking forward, Kevin Vallier in All the Kingdoms of the World presents the example of Mt. Athos, a self-governing peninsula of monasteries in Greece, as an example of an integralist microstate.5 Such states which govern themselves more consistently by Christian canons could co-exist with other more “worldly” states that govern themselves according to other principles. The relationship between these two types of societies balances the insufficiencies of both. A polity consistent with classical liberal principles of pluralism and voluntary human action, could provide a space for the world to voluntarily meet the model provided by the monastics.

The debate between a Christianity which participates in worldly institutions and one which flees them will not be settled by a principle, but by a person. Christ does not provide us with a list of rules to guide our life on earth, but an example to follow. Contemporary Christians should take time to set aside their philosophical tomes and instead dwell in the lives of the saints. John Chrysostom comes to mind. As bishop of Constantinople, he was expected to turn a blind eye to the intrigue and machinations of court politics, but instead stood against emperors and heretics taking control of church matters. Many saints, however, will go unrecognized in their lifetime. Monasticism helps draw attention to those who are too humble to draw attention to themselves. The practical instructions of the saints will seem myriad and even self-contradictory, but they are more honest to the incarnational tension we are called to live. The tension is best expressed by Eric Voegelin: “[T]he reality of existence, as experienced in the movement, is a mutual participation of human and divine.”6

Marcus Shera is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy at Chapman University. He is an economic historian who studies the relationship between religious and secular institutions. His primary work has been on the political economy of Christian monasticism and the limits of formal institutions. He is an Eastern Orthodox Christian. You can find more about his work at his website.

A friend (Nate Hile) also reminds me that in the chapter prior, the nations are also said to march with Satan and surround “the camp of the saints and the beloved city” (Revelation 20:7-10).

The narrative ultimately suggests that Jonah resists the calling to go to Nineveh out of his contempt for their sins.

Georges Florovsky, “Empire and Desert: Antinomies of Christian History,” Cross Currents 9, no. 3 (1959): 233–253. I recommend the book The Pacifist Option by Fr. Alexander Webster as an exploration of Florovsky’s essay applied to church tradition on pacifism and war.

Kingsnorth’s substack is somewhat dedicated to cataloging and visiting old monastic sites and holy wells in Ireland.

Kevin Vallier, All the Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

Eric Voegelin, “The Gospel and Culture,” in The Eric Voegelin Reader: Politics, History, Consciousness, ed. Charles R. Embry and Glenn Hughes (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2017), 261.

This is really great.

Too often even very great thinkers flatten the meaning of Christianity into its social teaching and politics or anti-politics.

Taking a broader view of Christianity as a religion allows for the legitimate diversities of politics and anti-politics throughout the history of the church.

Great article.

I also enjoyed reading the part of your dissertation that discussed the mendicant friars as historically navigating this civilizational dilemma. For example in there you included a quotation where David Hume lamented about how effective they were at "promoting their gainful superstitions" and one from Adam Smith praising them for their effective incentives to "animate the devotion of the common people."

I agree with you that there are too few examples of the religious life today as vocations have kept going down, especially in the West, but even then we are seeing the continued spiritual influence of the mendicants as successful evangelizers. For example, despite being a pretty tiny percentage of the overall number of priests in America, I constantly see friars on the most popular Catholic social media channels. For example Fr. Mark-Mary and other members of his order (Franciscan Friars of the Renewal) are all over the Ascension Presents YouTube channel that has over 1 million subscribers. The Dominicans (who are actually growing fast in America) such as Fr. Gregory Pine can also be seen in popular podcast episodes, many which have hundreds of thousands of views. Funny enough, both the Franciscan Friars of the Renewal and the Dominicans have friars that make popular folsky/bluegrass Catholic music that fill up music venues. So maybe the mendicants still have a place in walking the line between rejecting civilization and interacting with it.